Substantive Post #2: Models of Active Learning

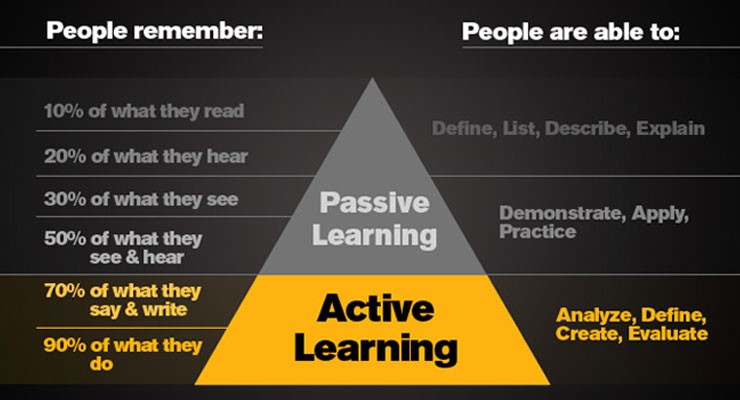

Models of active learning emphasize the idea that learners are producers of knowledge rather than passive consumers. Through systematic instructional frameworks, these models help instructors design learner-centered learning experiences instead of classrooms where students simply sit, listen, and take notes. The Models of Active Learning module points out that active learning not only enhances students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills, but also increases learning motivation and classroom engagement. Compared to traditional lecture-based instruction, active learning reduces the likelihood that students attend class without truly mastering the content and supports deeper conceptual understanding.

In my experience with learning through video games, many in-game learning supports reflect principles proposed by Mayer and Merrill. For example, game tutorials often apply the multimedia principle and the segmenting principle by using concise visual cues and step-by-step guidance to help players build an initial understanding of gameplay mechanics. However, in many cases games overlook the important coherence principle. Excessive visual scenes and lengthy background narratives that are not directly related to gameplay can interfere with novice learners’ understanding. This reflects what can be described as pre-activation stasis: when learners have not yet established a basic cognitive framework, excessive and complex information can hinder effective learning. At this stage, the sub-conscious principle also plays a role, only when perception and action gradually align can newly learned skills be performed fluently without constant conscious deliberation.

When designing an authentic classroom task using Merrill’s five instructional principles, I would choose an activity that requires learners to debug code in real time. Before the task, learners would review relevant prior knowledge through an interactive coding environment embedded in a web-based IDE (activation). Short instructional videos would then demonstrate effective debugging strategies (demonstration). Learners would apply these strategies by fixing errors themselves (application), followed by writing a brief reflection to connect the experience to future programming contexts (integration). This design supports active learning while ensuring that multimedia functions as a learning aid rather than a distraction.

The Historia video example provided by the instructor represents a low-tech approach to game-based learning. By incorporating multimedia elements such as interactive timelines, branching narrative choices at key moments, or audio narration, learners could explore cultural change through multiple pathways rather than passively watching a single linear presentation. This design further illustrates how media can support knowledge construction in active learning environments.

In Students Need to DO Something, the author argues that when students only read or listen, learning often remains superficial even if the information is complete. Hands-on practice, interaction, and physical engagement help make knowledge more concrete and transferable. This strongly resonates with my own K–12 experiences, particularly during my schooling in China, where traditional classrooms often emphasized listening and note-taking while offering limited opportunities for students to actively “do something.” Resistance to active learning in K–12 contexts may stem from time constraints, high-stakes standardized testing, and limited resources for teachers to design interactive activities.

Overall, models of active learning demonstrate that when multimedia is intentionally aligned with instructional goals and learning principles, it can enhance learner engagement and understanding rather than becoming a source of distraction.